FGD Scrubber Material - Material Description

ORIGIN

The burning of coal produces sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas. The 1990 Clean Air Act and subsequent amendments regulate SO2 emissions from burning coal. Coal fired power plants installed flue gas desulfurization (FGD) technology for reducing SO2 emissions. The two most common scrubber technology used today are wet or dry systems. Wet FGD systems introduce a spray of alkaline sorbent consisting of lime or limestone (primarily limestone) into the exhaust gas. The alkali reacts with the SO2 gas to form calcium sulfite (CaSO3) or calcium sulfate (CaSO4) that is collected in a liquid slurry form. The calcium sulfite or sulfate is allowed to settle out and the majority of the water is recycled. The settled material called FGD scrubber material or scrubber sludge is an off-white slurry with a solids content in the range of 5 to 10 percent. Because coal fired power plants typically have both a FGD systems and a fly ash removal system, fly ash is sometimes incorporated into the FGD material.Dry FGD systems use less water than wet systems and produce a dry by-product. The most common dry FGD system sprays slaked lime slurry into the flue gas. The main product of dry FGD systems is calcium sulfite with minor amounts of calcium sulfate.

Although made up of many technologies, approximately 85 percent of the FGD systems in the United States are categorized as wet systems, with the remaining 15 percent being considered dry systems.(1) The major difference in the FGD material produced from these two systems is the relative proportion of calcium sulfite and calcium sulfate. Calcium sulfite to sulfate proportion affects physical properties of FGD material, and with the many available FGD technologies there is a large variability in the characteristics of FGD material.(2)

Depending on the type of process and sorbent used, 20 to 90 percent of the available sulfur can be calcium sulfite with the remaining portion being calcium sulfate. FGD material with high concentrations of sulfite pose dewatering problem. Sulfite sludges settle and filter poorly and are thixotropic (a thixotropic material appears as a solid, but will liquefy when vibrated or agitated). High sulfite FGD material is generally not suitable for either use or disposal without treatment. Treatment can include forced oxidation, dewatering, and/or fixation or stabilization.

In a wet FGD system, natural oxidation occurs when only the oxygen in the flue gas is available to react. This method primarily produces calcium sulfite. Forced oxidation in a wet FGD system supplies additional oxygen through blowers that produces calcium sulfate, generally in the form of gypsum (CaSO4×H20). Forced oxidation is becoming increasingly popular due to the economic applications of gypsum, primarily in wallboard production.(3) Calcium sulfate grows to a larger crystal size than calcium sulfite. As a result, calcium sulfate can be more readily filtered or dewatered to a stable material than can calcium sulfite sludge.(4) Centrifuges or belt filter presses are typically used to dewater FGD scrubber material.

Fixation and stabilization are terms that are often used interchangeably when referring to FGD sludge treatment. In general, stabilization of FGD scrubber material refers to the addition of dry material, such as fly ash, to the dewatered FGD filter cake. The FGD-dry material mixture is stabilized to the point that the material can be handled and transported by conventional construction equipment without water seepage. In addition, the mixture of FGD and dry material should be stable enough to support compaction machinery. Fly ash to filter cake ratios should be 1:1 to allow for transportation and handling, although a dryer 2:1 ratio can be requested.(5)

Fixation ordinarily refers to the addition of chemical reagent(s) to solidified stabilized FGD scrubber material to sufficient strength to satisfy structural specifications. This can involve the addition of Portland cement, lime, or self-cementing fly ash to induce both physical and chemical reactions between the stabilized sludge filter cake and the reagents. Typically fixation is accomplished by adding quicklime and pozzolanic fly ash. Figure 1 presents an illustration of FGD processing, reuse, or disposal options.

Figure 1. FGD sludge processing system.(6)

Additional information on coal ash production and use in the United States can be obtained from:American Coal Ash Association (ACAA)

15200 E. Girard Ave., Ste. 3050

Aurora, CO 80014-3955

http://www.acaa-usa.org/

Coal Combustion Products Partnership (C2P2)

Office of Solid Waste (5305P)

1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20460

http://www.epa.gov/epaoswer/osw/conserve/c2p2/index.asp

Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI)

3412 Hillview Road

Palo Alto, California 94304

http://my.epri.com/

Edison Electric Institute (EEI)

1701 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004-2696

http://www.eei.org/

Green Highways Partnership

http://www.greenhighways.org/index.cfm

AASHTO Center for Environmental Excellence

444 North Capitol Street, NW Suite 249

Washington, D.C., 20001

202-624-5800

http://environment.transportation.org/

CURRENT MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

RecyclingIn 2006, FGD scrubber systems at coal-fired power plants generated approximately 27.4 million metric tons (30.2 million tons) of material, or 24.2 percent of all coal combustion products.(7) Due to an expected increase in scrubbing applications, the amount of FGD produced is expected to grow during the next few decades.(2)

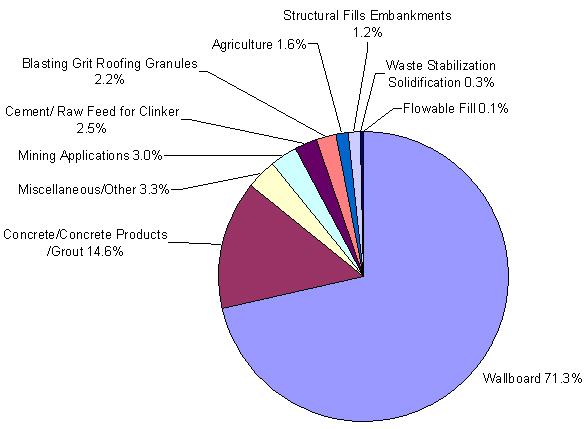

Approximately 30 percent of the FGD material produced in 2006 was beneficially used.(7) Fixated or stabilized calcium sulfite FGD scrubber material has been used as an embankment and road base material. FGD products have also been used in place of gypsum, as feed material for the production of Portland cement. In addition, FGD material has been used in flowable fill in mine reclamation and in aerated concrete blocks. Oxidized FGD scrubber material (calcium sulfate high in gypsum content) is used in the manufacturing of wallboard.(3) For use as wallboard gypsum, oxidized FGD scrubber material only requires drying to a specified solids content and does not require fixation or stabilization. Wallboard production represents the largest single market for FGD scrubber material.(7)

Use of FGD material has increased over the past decade because FGD material is being used as a source of gypsum for wallboard and Portland cement production. There was a 5 percent increase in the utilization of FGD material between 2005 and 2006, representing an additional 453,000 metric tons (500,000 tons) of material.(7) Figure 2 illustrates common applications of FGD material.

Figure 2. FGD applications as a percentage of total FGD material used in 2006.(7)

DisposalWhen FGD material cannot be used economically, the by-product is stored in surface impoundments and then landfilled. Stabilization or fixation and placement in landfills is the most common method of disposal.

State Regulations and Specifications

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has delegated responsibility to the states to ensure that coal combustion by-products are properly used. Each state, therefore, has individual specifications and environmental regulations. A map from the National Energy Technology Laboratory that links to a database of state regulations on the utilization and disposal of coal combustion by-products can be found here.

The state regulations database contains summary information on current regulations in each state and contact information for individuals with regulatory responsibility. A site maintained by the U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) contains a searchable library for all highway specifications across the country. This can be found here.

MARKET SOURCES

Fixated FGD scrubber material is generated, dewatered, and stabilized at coal-burning power plants that require scrubbing of flue gas to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions. Plants that require scrubbing typically burn either medium- or high-sulfur coal. For FGD scrubber sludge to be a useable construction material, the sludge must first be dewatered and then stabilized or fixated. Even for landfilling, scrubber sludge must be dewatered and stabilized to allow for transport, placement, and compaction.Fixated or stabilized calcium sulfite FGD sludge can have a solids content from 55 to 80 percent, depending on the amount of added fly ash. The resultant fixated FGD sludge product is a damp, gray, silty, compactable material capable of developing sufficient compressive strength to support construction equipment.(8)

The majority of coal-fired power plants that are equipped with FGD scrubber systems, dewater and stabilize FGD scrubber sludge for beneficial use or landfilling. Dewatering and stabilization is typically done by the utility company, while loading, transporting, and placement of stabilized or fixated FGD scrubber material is typically done by an ash management contractor. Stabilized or fixated FGD scrubber material can be obtained from either a power plant having FGD scrubbers or an ash management contractor. Most coal-burning electric utility companies currently employ an ash management specialist whose responsibility is to monitor ash generation, quality, use, or disposal, and to interface with ash marketers. To identify an FGD material source, contact the local utility company or visit the American Coal Ash Association's web site at the link provided above.

HIGHWAY USES AND PROCESSING REQUIREMENTS

Stabilized BaseStabilized or fixated FGD scrubber material is used for road base construction around the country, for example in Florida, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Texas.(9;10;11;12) Stabilization or fixation of FGD scrubber material (especially calcium sulfite sludge) is accomplished with the addition of quicklime and pozzolanic fly ash, Portland cement, or self-cementing fly ash. Other activators may be used in place of quicklime. FGD scrubber sludge is dewatered before the addition of stabilization or fixation reagents. Additional fixation reagents, above the amount added for stabilizing for landfilling, may be needed for stabilized base construction in order to meet compressive strength or durability requirements.

Flowable Fill

Flowable fill is a slurry mixture consisting of sand or other fine aggregate material and a cementitious binder that is normally used as substitute for a compacted earth backfill. FGD may be used as a fine aggregate in flowable fill.

Embankments

FGD material can be used for embankment construction and reconstruction of failed slopes(13). As an embankment or fill material, stabilized FGD material is used as a substitute for natural soils. Stabilized compacted FGD material have a high shear strength to unit weight ratio, hence embankments constructed of these materials have higher slope stability factors, steeper permissible slopes, and result in reduced settlement of underlying soils as compared to fills with natural soils. (13)

In Pennsylvania in 1989 FGD material reclaimed from a landfill was used in conjunction with fly ash in an embankment project. Other than fly ash, no additional reagents were needed to develop adequate strength for the embankment construction.(14) In 1996, Ohio State Route 83 was repaired by constructing a high-strength FGD wall through the failure plane of a rotational slide to prevent further slippage of a highway embankment. The FGD material used in this application developed sufficient strength and was easy to install.(15)

MATERIAL PROPERTIES

Physical PropertiesDewatered and fixated calcium sulfite FGD scrubber material can be used for transportation applications, while the calcium sulfate FGD scrubber material is frequently used for wallboard or as a cement additive. Calcium sulfate FGD scrubber material can also be used in transportation applications. Table 1 shows the difference in particle size between calcium sulfite and calcium sulfate FGD scrubber material.(16) The calcium sulfite material (unoxidized) is finer with a higher specific gravity than the calcium sulfate material (oxidized). The specific gravity of both calcium sulfite and sulfate is less than natural soil, which is approximately 2.7. Calcium sulfite rich FGD material can be expected to have a specific gravity of approximately 2.57, where calcium sulfate rich FGD material is expected to have a lower specific gravity of approximately 2.36.(16)

Table 1. Typical grain size properties of FGD scrubber material.(16)

|

Property |

Calcium Sulfite (Unoxidized) |

Calcium Sulfite (Oxidized) |

|

Particle Sizing |

% |

% |

|

Sand Size Silt Size Clay Size |

1.3 90.2 8.5 |

16.5 81.3 2.2 |

The degree to which wet FGD scrubber material is treated (i.e. dewatered, stabilized, and fixated) influences the physical properties. Table 2 shows the physical characteristics of typical calcium sulfite FGD scrubber material in a dewatered, physically stabilized, and fixated condition. Basic physical properties include solids content, moisture content, and wet and dry unit weight.(17) Dewatered calcium sulfite FGD sludges are a soft filter cake with a solids content typically in the range of 40 to 65 percent. Calcium sulfate FGD sludges can be dewatered more easily than sulfite sludges and may achieve solids contents as high as 70 to 75 percent.(18)

Table 2. Physical characteristics of typical calcium sulfite FGD scrubber material.(16;17)

|

Physical Property |

Dewatered |

Stabilized |

Fixated |

|

Solids Content (%) |

40 - 65 |

55 - 80 |

60 - 80 |

|

Wet Unit Weight (kN/m3) (lb/ft3) |

14.9 - 15.7 (95 - 100) |

14.1 - 17.3 (90 - 110) |

14.1 - 18.1 (90 - 115) |

|

Dry Unit Weight (kN/m3) (lb/ft3) |

9.4 - 10.2 (60 - 65) |

9.4 - 13.3 (60 - 85) |

12.6 - 15.7 (80 - 100) |

Dewatered and unstabilized calcium sulfite FGD scrubber sludge consists of fine silt-clay sized particles with approximately 50 percent finer than 0.045 mm (No. 325 sieve). This material has a dry unit weight in the range of 9.43 to 12.58 kN/m3 (60 to 80 lbs/ft3), with a specific gravity in the range of 2.4.(17)

Depending on the amount of fly ash in a stabilized blend, maximum dry unit weight values of fixated FGD scrubber material can range from 10.4 to 12.4 kN/m3 (66 to 79 lb/ft3) at optimum moisture contents ranging from 27 to 37 percent when tested using the standard Proctor (ASTM D698)(19)test method.(5) Higher proportions of fly ash yield a higher maximum density.(5)

For most dry FGD systems, the FGD by-product is a fine material of uniform consistency with between 56 and 90 percent of the particles having a diameter smaller than 0.025 mm.(20) Grain size uniformity coefficients are in the range of 1.8 to 2.4 which represents a uniform particle size. The specific surface area, ranging from 1.28 to 9.49 m2 g-1, indicates a nonporous material.(20) Swell tests conducted according to Method A of ASTM D4546(21) on dry FGD samples showed a high degree of variability in swelling, in the range of 0 to 60 percent. Swelling observed over time indicates two distinct swelling episodes. The first episode occurs immediately after the introduction of water and produces a 0 to 14 percent volume change. The second episode typically begins 10 to 50 days after the introduction of water and accounts for the remaining swell.(2)

Chemical Properties

Chemically, FGD material is dominated by Ca, S, Al, Fe, and Si and accompanied by minor elements (i.e., As, Co, Cu, Mo, Ni, P, Se, and Sr). Unlike fly ashes or bottom ashes, neither the parent coal nor the boiler conditions have a significant effect on the physical or chemical properties of the FGD byproducts. Instead, the characteristics of the FGD byproducts are strongly controlled by the type of reagent used, the operating temperature, pressure, and degree of oxidation within the scrubbing unit and the amount of water used to distribute the reagent through the flue gas.(22) Tables 3 and 4 outline the major and minor element concentrations in typical dry FGD products.

Table 3. Range of average concentration of major elements in dry FGD material (g/kg).(20)

|

Ca |

122 - 312 |

|

S |

41 - 126 |

|

Al |

13 - 74 |

|

K |

1 - 9 |

|

Si |

25 - 139 |

|

Mg |

6 - 92 |

|

Fe |

2 - 110 |

Table 4. Range of average concentration of minor elements in dry FGD material (mg/kg).(20)

|

As |

44.1 - 186 |

Mo |

8.6 - 25.5 |

|

B |

145 - 418 |

Ni |

29.0 - 80.6 |

|

Be |

1.6 - 15.1 |

P |

220 - 601 |

|

Cd |

1.7 - 4.9 |

Pb |

11.3 - 59.2 |

|

Co |

8.9 - 45.6 |

Se |

3.6 - 15.2 |

|

Cr |

16.9 - 76.6 |

Sr |

308 - 565 |

|

Cu |

30.8 - 251 |

V |

20.1 - 122 |

|

Li |

11.4 - 84.7 |

Zn |

108 - 208 |

|

Mn |

127 - 207 |

Lime and limestone are used as a reagent in 90 percent of FGD systems in the United States.(3) Table 5 lists the major components of FGD scrubber material prior to fixation for different sorbent materials and natural or forced oxidation processes.(16) Except for FGD material subjected to forced oxidation, sludges from the scrubbing of bituminous coals are generally sulfite-rich, whereas forced oxidation sludges, and sludges generated from scrubbing of subbituminous and lignite coals, are sulfate-rich. Fly ash is a principal constituent of FGD scrubber material only if the scrubber serves as a particulate control device in addition to SO2 removal or if separately collected fly ash is mixed with the sludge.(16)

As shown in Table 5, the use of limestone as a sorbent with bituminous coals results in significantly lower percentages of calcium sulfite and higher percentages of calcium sulfate and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) than the use of lime as a sorbent with bituminous coals.

Table 5. Major components of FGD scrubber material from different coal types and scrubbing processes (percent by weight).

|

Type of Process |

Type of Coal |

Sulfur Content |

CaSO3 |

CaSO4 |

CaCO3 |

Fly Ash |

|

Lime (Natural Oxidation) |

Bituminous |

2.9 - 4.0 |

50 - 94 |

2 - 6 |

0 - 3 |

4 - 41 |

|

Lime (Forced Oxidation) |

Bituminous |

2.0 - 3.0 |

0 - 3 |

52 - 65 |

2 - 5 |

30 - 40 |

|

Limestone (Natural Oxidation) |

Bituminous |

2.9 |

19 - 23 |

15 - 32 |

4 - 42 |

20 - 43 |

|

Limestone (Natural Oxidation) |

Subbituminous |

0.5 - 1.0 |

0 - 20 |

10 - 30 |

20 - 40 |

20 - 60 |

|

Dual Alkali (Ca-Na) (Natural Oxidation) |

Bituminous |

1.0 - 4.0 |

65 - 90 |

5 - 25 |

2 - 10 |

0 |

|

Fly Ash (Class C) (Natural Oxidation) |

Lignite |

0.6 |

0 - 5 |

5 - 20 |

0 |

40 - 70 |

The primary mineral phases of fixated FGD include hannebachite (CaSO3×0.5 H2O), mullite (Al6Si2O13), quartz (SiO2), hematite (Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), glass, and ettringite [Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12× 26H2O].(23)

The pH of dry FGD products is highly alkaline (9.9 to 12.6) and is primarily affected by the sorbent. The high pH values are due to the presence of oxides and hydroxides of Ca and Mg which convert to carbonates when exposed to water and CO2. This results in a decrease in pH over time.(20)

Mechanical Properties

Mechanical properties of FGD material are listed in Table 6 including: shear strength, unconfined compressive strength, and hydraulic conductivity. The expected range of these mechanical properties is presented for dewatered, stabilized, and fixated calcium sulfite FGD scrubber material.

Table 6. Mechanical properties of calcium sulfite FGD scrubber material. (8;16;12);24;25)

|

Mechanical Property |

Dewatered |

Stabilized |

Fixated |

|

Internal Friction Angle |

20° |

35° – 45° |

35° – 45° |

|

28-Day Unconfined Compressive Strength (kPa) (psi) |

- - |

170 – 340 (25 – 50) |

340 – 1380 (50 – 200) |

|

90-Day Unconfined Compressive Strength (kPa) (psi) |

- - |

- - |

980 – 4600 (142 – 667) |

|

Hydraulic conductivity (cm/sec) |

10-4 to 10-5 |

10-6 to 10-7 |

10-6 to 10-8 |

Dewatered unstabilized calcium sulfite FGD scrubber sludge is a pastelike material with low shear strength and little bearing capacity. This material is thixotropic and reverts to a liquid or slurry form when agitated. In a Dewatered unstabilized form, this material has no unconfined compressive strength, an angle of internal friction approximately 20°, and a hydraulic conductivity in the range of 10-4 to 10-5 cm/sec.(12)

Stabilized or fixated calcium sulfite FGD scrubber material has 28-day unconfined compressive strength in the range of 170 to 1380 kPa (25 to 200 lb/in2lb/in2), 90-day unconfined compressive strength in the range of 990 to 4600 kPa (142 lb/in2 to 573 lb/in2), an angle of internal friction of 35° to 45°, and a hydraulic conductivity in the range of 10-6 to 10-8 cm/sec.(8;24;25)

When stabilized or fixated FGD scrubber sludge is used for road base construction, the unconfined compressive strength is typically in the range of 1720 to 6900 kPa (250 to 1000 lb/in2) and can be adjusted to meet specifications by adjusting the amount of reagent in a blend. The flexural strength of stabilized FGD sludge road base materials is normally in the 690 to 1720 kPa (100 to 250 lb/in2) range.(24) To achieve these strength ranges, fixation reagents such as Portland cement, lime, or fly ash are typically required.

FGD gypsum (calcium sulfate) is most commonly used in wallboard production, although laboratory data indicates that stabilized FGD gypsum mixtures should perform satisfactorily in transportation applications. Unstabilized dewatered FGD gypsum can have a 28-day unconfined compressive strength of between 213 to 358 kPa (31 to 52 lb/in2).(26) Cement stabilized gypsum has been shown to develop 7-day unconfined compressive strength between 1400 to 4600 kPa (200 to 670 lb/in2) depending on cement content and compaction effort.(27)

Resilient modulus tests conducted on mixtures of FGD gypsum stabilized with 6 and 8 percent Type II cement, at a bulk stress of 590 kPa (86 psi), had a resilient modulus of 3,800,000 kPa (550,000 psi) for 6 percent Type II cement and 12,000,000 kPa (1,750,000 psi) for 8 percent Type II cement.(27) Comparing these results against typical base materials, on the basis of the resilient modulus data, stabilized FGD gypsum blends should perform as well as any other conventional base materials.(27)

ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

LeachabilityOne of the main limitations of present leach test methods is that these methods do not consider the material application. For example, use of coal combustion products in Wisconsin is regulated by Ch. NR 538 of the Wisconsin Administrative Code. This regulation requires water leaching tests (WLT) of material in bulk form, but does not consider mixtures, such as FGD material in flowable fill. In addition, WTL does not necessarily model leachate produced in the field. The WLT indicates the potential for trace element release from bulk coal combustion products, but does not evaluate how a leachate will impact groundwater.(28)

Five widely used standard leaching tests are outlined in Table 7.

Table 7. Extraction conditions for different standard leaching tests.(28)

|

Test Procedure |

Method |

Purpose |

Leaching Medium |

Liquid-Solid Ratio |

Particle Size |

Time of Extraction |

|

Water Leach Test |

ASTM D3987-06 |

To provide a rapid means of obtaining an aqueous extract |

Deionized water |

20:1 |

Particulate or monolith as received |

18 hr |

|

TCLP |

EPA SW-846 Method 1311 |

To compare toxicity data with regulatory level. RCRA requirement. |

Acetate buffer* |

20:1 |

< 9.5 mm |

18 hr |

|

Extraction Procedure Toxicity (EP Tox) |

EPA SW-846 Method 1310 |

To evaluate leachate concentrations. RCRA requirement. |

0.04 M acetic acid (pH = 5.0) |

16:1 |

< 9.5 mm |

24 hr |

|

Multiple Extraction Procedure |

EPA SW-846 Method 1320 |

To evaluate waste leaching under acid condition |

Same as EP Toxicity, then at pH = 3.0 |

20:1 |

< 9.5 mm |

24 hr extraction per stage |

|

Synthetic Precipitation Leaching Procedure (SPSL) |

EPA SW-846 Method 1312 |

For waste exposed to acid rain |

DI water, pH adjusted to 4.2 to 5 |

20:1 |

< 9.5 mm |

18 hr |

| * Either an acetate buffered solution with pH = 5 or acetic acid with pH = 3.0 | ||||||

Leachate studies on dry FGD material show pH typically exceeds 11.0, and some sources can exceeded the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act limit of 12.5 for toxic waste, although this high leachate pH is expected to decrease over time.(20;29) Total dissolved solids mainly consist of Ca, SO42-, and SO32- and can exceed secondary drinking water standards for total dissolved solids (500 mg L-1) and sulfate (250 mg L-1).(20) Trace element concentrations in FGD leachate are generally low.(20)

One study investigated the potential of replacing clay with FGD in low permeability liners. This study used a lime-enriched, fixated FGD material on a full-scale design and evaluated the leaching potential over a 5½-year period. Maximum concentrations of elements measured during this time met all Ohio nontoxic criteria, and generally met all national primary and secondary drinking water standards. In addition, retention of As, B, Cr, Cu, and Zn was observed and likely due to constituent sorption to mineral components in the FGD material.(29)

The results of extraction procedure toxicity leachate tests indicate that fresh or stabilized FGD gypsum will meet EPA Leachate Standards.(27)

Modeling

Models currently used to simulate leaching from pavement systems and potential impacts to groundwater include STUWMPP,(30) IMPACT,(31)HYDRUS-2D,(32)(33)(34) WiscLEACH,(35) and IWEM.(36) Among these models STUWMPP, IMPACT, WiscLEACH and IWEM are in the public domain. STUWMPP employs dilution–attenuation factors obtained from the seasonal soil compartment (SESOIL) model to relate leaching concentrations from soils and byproducts to concentrations in underlying groundwater. IMPACT was specifically developed to assess environmental impacts from highway construction. Two dimensional flow and solute transport are simulated by solving the advection dispersion reaction equation using the finite difference method.(35).

WiscLEACH combines three analytical solutions to the advection-dispersion-reaction equation to assess impacts to groundwater caused by leaching of trace elements from coal combustion products used in highway subgrade, subbase and base layers. WiscLEACH employs a user friendly interface and readily available input data along with an analytical solution to produce conservative estimates of groundwater impact.(35)

The U.S. EPA's Industrial Waste Management Evaluation Model (IWEM), although developed to evaluate impacts from landfills and stock piles, can help in determining whether ash leachate will negatively affect groundwater. IWEM inputs include site geology/hydrogeology, initial leachate concentration, metal parameters, and regional climate data. Given a length of time, the program will produce a leachate concentration at a control point (such as a pump or drinking well) that is a known distance from the source. In addition, Monte Carlo simulations can provide worst-case scenarios for situations where a parameter is unknown or unclear. In comparing IWEM to field lysimeter information, IWEM over predicted the leachate concentrations and could be considered conservative. Overall, however, IWEM performed satisfactorily in predicting groundwater and solute flow at points downstream from a source.(37) A byproducts module for IWEM will be offered by the EPA in the near future.

A source for information on assessing risk and protecting groundwater is the EPA's "Guide for Industrial Waste Management" (38) which can be found here.

REFERENCES

A searchable version of the references used in this section is available here. A searchable bibliography of FGD scrubber material literature is available here.- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Air pollution control technology fact sheet flue gas desulfurization (FGD) - wet, spray dry, and dry scrubbers. Report nr EPA-452/F-03-034, U.S. EPA; Washington, DC: 2003.

- Bigham JM, Kost DA, Stehouwer RC, Beeghly JH, Fowler R, Traina SJ, Wolfe WE, Dick WA. Mineralogical and engineering characteristics of dry flue gas desulfurization products. Fuel 2005;84:1839-48.

- Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). Flue gas desulfurization by-products: Composition, storage, use, and health and environmental information. EPRI, Inc; Palo Alto, CA: 1999.

- Taha R, Saylak D. The use of flue gas desulfurization gypsum in civil engineering applications. In: Proceedings of utilization of waste materials in civil engineering construction. American Society of Civil Engineers; 1992.

- Butalia TS, Wolfe WE. Evaluation of permeability characteristics of FGD materials. Fuel 1999;78:149-52.

- Duvel WA, Afwood RA. FGD sludge disposal manual. Report nr FP-977, Research Project 786-1, Electric Power Research Institute; Palo Alto, CA: 1979.

- American Coal Ash Association (ACAA). 2006 coal combustion product (CCP) production and use. American Coal Ash Association; Aurora, CO, 2007.

- Smith CL. FGD sludge disposal consumes over eight million tons of fly ash yearly. In: Proceedings of the seventh international ash utilization symposium, Orlando, FL. Department of Energy; Washington, DC: 1985.

- Smith CL. First 100,000 tons of stabilized scrubber sludge in roadbase construction. In: Second international exhibition and conference for the power generation industries - POWER-GEN '89, New Orleans, LA. 1989.

- Smith CL. FGD sludge C coal ash road base: Seven years of performance. In: Proceedings of the 8th international coal and solid fuels utilization conference, Pittsburgh, PA. 1985.

- Amaya PJ, Booth EE, Collins RJ. Design and construction of roller compacted base courses containing stabilized coal combustion by-product materials. In: Proceedings of the 12th international symposium on management and use of coal combustion by-products. Electric Power Research Institute; Palo Alto, CA: 1997.

- Prusinski JR, Cleveland MW, Saylak D. Development and construction of road bases from flue gas desulfurization material blends. In: Proceedings of the eleventh international ash utilization symposium. CA: Electric Power Research Institute; Palo Alto, 1995.

- Butalia TS, Wolfe WE. Market opportunities for utilization of Ohio flue gas desulfurization (FGD) and other coal combustion products (CCPs). The Ohio State University; Columbus, OH: 2000.

- Brendel GF, Glogowski PE. Ash utilization in highways: Pennsylvania demonstration project. Report nr GS-6431. Electric Power Research Institute; Palo Alto, California:1989.

- Payette RM, Wolfe WE, Beeghly J. Use of clean coal combustion by-products in highway repairs. Fuel 1997;76:749-53.

- Smith CL. FGD waste engineering properties are controlled by disposal choice. In: Proceedings of conference on utilization of waste materials in civil engineering construction, New York, NY, American Society of Civil Engineers; 1992.

- Patton RW. Disposal and treatment of power plant wastes. Presented at the society of mining engineers fall meeting, Salt Lake City, UT. 1983.

- Smith CL. 15 million tons of fly ash yearly in FGD sludge fixation. In: Proceedings of the tenth international ash utilization symposium. Electric Power Research Institute; Palo Alto, CA: 1993.

- ASTM D698-07e1 standard test methods for laboratory compaction characteristics of soil using standard effort (12 400 ft-lbf/ft3 (600 kN-m/m3)). In: Annual book of ASTM standards. ASTM; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2007.

- Kost DA, Bigham JM, Stehouwer RC, Beeghly JH, Fowler R, Traina SJ, Wolfe WE, Dick WA. Chemical and physical properties of dry flue gas desulfurization products. Journal of Environmental Quality 2005;34:676.

- ASTM D4546-03 standard test methods for one-dimensional swell or settlement potential of cohesive soils. In: Annual book of ASTM standards. ASTM; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2003.

- NETL National Energy Technology Laboratory. Commercial use of coal utilization by-products and technology trends. Department of Energy Office of Fossil Energy; Washington, DC: 2003.

- Laperche V, Bigham JM. Quantitative, chemical, and mineralogical characterization of flue gas desulfurization by-products. Journal of Environmental Quality 2002;31:979-88.

- Smith CL. Case histories in full scale utilization of fly ash - fixated FGD sludge. In: Proceedings of the ninth international ash utilization symposium. Electric Power Research Institute; Palo Alto, CA: 1991.

- Solem-Tishmack JK, McCarthy GJ, Docktor B, Eylands KE, Thompson JS, Hassett DJ. High-calcium coal combustion by-products: Engineering properties, ettringite formation, and potential application in solidification and stabilization of selenium and boron. Cement and Concrete Research 1995;25:658-70.

- Ramme BW, Tharaniyil M. Coal combustion products utilization handbook. We Energies; Milwaukee, WI: 2004.

- Taha R. Environmental and engineering properties of flue gas desulfurization gypsum. Transportation Research Record 1993;1424.

- Bin-Shafique MS, Benson CH, Edil TB. Geoenvironmental assessment of fly ash stabilized subbases. Geo Engineering Report No. 02-03, University of Wisconsin – Madison; Madison, WI: Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering; 2002.

- Cheng C-, Tu W, Zand B, Butalia TS, Wolfe WE, Walker H. Beneficial reuse of FGD material in the construction of low permeability liners: Impacts on inorganic water quality constituents. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2007;133(5):523-31.

- Friend M, Bloom P, Halbach T, Grosenheider K, Johnson M. Screening tool for using waste materials in paving projects (STUWMPP). Report nr MN/RC–2005-03. Office of Research Services, Minnesota Dept. of Transportation, Minnesota; 2004.

- Hesse TE, Quigley MM, Huber WC. User’s guide: IMPACT- A software program for assessing the environmental impact of road construction and repair materials on surface and ground water. NCHRP 25-09, NCHRP; 2000.

- Simunek J, Sejna M, van Genuchten, M. T. The HYDRUS-2D software package for simulating the two-dimensional movement of water, heat, and multiple solutes in variably-saturated media. Report nr. IGWMC - TPS – 53, International Ground Water Modeling Center; Golden, Colorado, 1999.

- Bin-Shafique MS, Benson CH, Edil TB. Leaching of heavy metals from fly ash stabilized soils used in highway pavements. Report nr 02-14. University of Wisconsin-Madison, Geo Engineering Program, Madison, WI, 2002.

- Apul D, Gardner K, Eighmy T, Linder E, Frizzell T, Roberson R. Probabilistic modeling of one-dimensional water movement and leaching from highway embankments containing secondary materials. Environmental Engineering Science 2005;22(2):156–169.

- Li L, Benson CH, Edil TB, Hatipoglu B. Groundwater impacts from coal ash in highways. Waste and Management Resources 2006;159(WR4):151-63.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Industrial waste management evaluation model (IWEM) User’s guide. Report nr EPA530-R-02-013, US EPA; Washington, DC: 2002.

- Melton JS, Gardner KH, Hall G. Use of EPA’s industrial waste management evaluation model (IWEM) to support beneficial use determinations. U.S. EPA Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response (OSWER); 2006.

- Guide for Industrial Waste Management [Internet]; c2006. Available from: http://www.epa.gov/epaoswer/non-hw/industd/guide/index.asp.

FGD Scrubber Material - Stabilized Base

INTRODUCTION

Fixated or stabilized flue gas desulfurization (FGD) scrubber material can be used as a stabilized base or subbase material in the same manner as lime-fly ash or cement-stabilized base materials. Fixated FGD scrubber material may be used in an "as produced" condition, provided the material meets specifications, or the FGD scrubber material can be modified with additional reagents such as Portland cement, lime, fly ash, etc. to improve characteristics. In addition to adding fixation reagents, an aggregate material (sometimes coal bottom ash) can be blended with the fixated FGD scrubber material to improve material performance. Properly designed fixated FGD scrubber material has comparable strength development and durability characteristics to that of conventional stabilized base materials.PERFORMANCE RECORD

According to a 2005 coal combustion product use survey, 12 states have specifications for soil stabilization, which includes stabilized base and subbase materials.(1) FGD scrubber material has been employed as a component in stabilized base and subbase material since the 1970's. Typically dewatered FGD material is combined with fly ash or cement, lime, and aggregate, which is often coal bottom ash. The FGD base mixture is placed and compacted to thicknesses between 150 to 300 mm (6 to 12 in) and then overlaid with a wearing surface. With proper construction, FGD material used in stabilized base applications has performed successfully.In Florida, crushed lime rock is commonly used as a road base construction material. Laboratory results indicated that base course compositions of lime, fly ash, and dewatered FGD scrubber sludge (referred to as Poz-o-Tec) had better bearing strength characteristics than lime rock base.(2)Between 1977 and 1989, 12 FGD base course projects were constructed in central Florida. The base course thicknesses for these projects varied from 150 to 300 mm (6 to 12 in). Performance was reported as highly satisfactory.(2)

In 1977, a 244 m (800 ft) long section of pozzolanic road base material composed of lime, fly ash, bottom ash, and dewatered FGD scrubber material was placed as a demonstration on a state secondary road in southwestern Pennsylvania. The entire base was placed in one day in a single lift at a compacted thickness of 250 mm (10 in). The base was covered by a 50 mm (2 in) bituminous concrete binder course and a 25 mm (1 in) bituminous concrete wearing surface. Test data and visual observations over a 7 year period following installation demonstrated successful performance. Despite severe freeze-thaw cycles, the road exhibited no potholes or broken areas and the base remained intact as verified by periodic coring. The average unconfined compressive strength of road base cores was 4960 kPa (720 lb/in2) after 1 year, 5800 kPa (840 lb/in2) after 3 years, and 6990 kPa (1014 lb/in2) after 7 years.(3)

In 1995, a 77 m (250 ft) test section of cement, bottom ash, and fixated FGD scrubber sludge base material was placed as part of a demonstration haul road at the Gavin power plant in Cheshire, Ohio. The base course mix design involved a blend of 40 percent bottom ash and 60 percent fixated FGD scrubber sludge to which 7 percent Portland cement was added. The base course mix was produced in a pugmill mixing plant.(4) The FGD material base course was compacted to a thickness of 200 mm (8 in) and overlaid with 75 mm (3 in) of asphalt paving. The haul road was used extensively by heavy trucks on a daily basis and was evaluated more than al year after installation and showed no noticeable signs of distress.(4)

Two demonstration test sections, each 92 m (300 ft) long and 300 mm (12 in) thick, were constructed in 1993 at the Riverside Campus of Texas A&M University. The first test section consisted of a blend of self-cementing fly ash and dewatered FGD sludge (fixated FGD materail), coal bottom ash and additional self-cementing fly ash. The second test section consisted of the fixated FGD material blended with type II Portland cement.(5) The test sections were constructed by spreading the component materials with a motor grader and mixing in place with a pulvi-mixer. A control section, also 93 m (300 ft) long, was also placed between the two test sections. The control section consisted of 300 mm (12 in) of crushed iron ore gravel. After 2 years of monitoring, both of the FGD scrubber sludge base sections demonstrated significantly higher strength and stiffness than the control section.(5)

An additional FGD base course test section was constructed at the Riverside Campus of Texas A&M University in 1999. This research focused on reducing sulfate attack and swelling by using high volume fly ash cement (58 percent Class F fly ash to 42 percent Type I Portland cement) in a FGD stabilized base mix. The FGD base mix consisted of 50 percent bottom ash, 40 percent FGD scrubber material, and 10 percent high volume fly ash cement. This research demonstrated that this FGD base course could be employed under high volume traffic conditions and the use of the high volume fly ash cement reduced the cement demand by 58 percent while at the same time reducing sulfate attack and expansion.(6)

MATERIAL PROCESSING REQUIREMENTS

Material from dry FGD systems is handled in a similar manner as fly ash. Dry FGD material may need moisture content conditioning (to approximately 10 percent) prior to transportation to reduce dusting.(7) Wet FGD material requires dewatering and fixation, which typically occur at the power plant, before transport and use in stabilized base material.Dewatering

The calcium sulfite scrubber material from wet FGD systems is generally of toothpastelike consistency (from 25 to 50 percent solids) after dewatering. Dewatering is usually accomplished by belt filter presses or centrifuges. Centrifuges are normally able to dewater the sludge to a higher solids content than filter presses.

Stabilization/Fixation

Dewatered FGD material must be stabilized or fixated by the addition of dry reagents (quicklime and Class F fly ash, Class C fly ash, or Portland cement) before being use in stabilized base compositions. The fixated wet FGD sludge should have a solids content of at least 65 percent prior to compaction. The material can then be placed and compacted as a base material or blended with additional reagent, natural aggregate, or bottom ash to meet strength and durability requirements.

ENGINEERING PROPERTIES

FGD scrubber material properties of interest when using FGD material in stabilized bases and subbases include particle size distribution, moisture content, wet and dry density, hydraulic conductivity, compaction characteristics, compressive strength, resilient modulus, and durability.Particle Size Distribution :For most dry FGD systems, the FGD by-product is a fine material of uniform consistency with between 56 and 90 percent of the particles having a diameter smaller than 0.025 mm.(8) Grain size uniformity coefficients for dry FGD material are in the range of 1.8 to 2.4, which represent a uniform particle size. The particle size distribution and uniformity indicates that dry FGD material can be classified as a silt-sized material.(7;8)

Dewatered and unstabilized calcium sulfite FGD material consists of fine silt-clay sized particles with approximately 50 percent finer than 0.045 mm (No. 325 sieve). Calcium sulfate FGD material is more course and is classified as a silt with sand. At temperatures above 100 c, calcium sulfate particles have been observed to degrade; therefore, oven drying FGD calcium sulfate can effect the particle size distribution.(9) Particle size information for wet FGD material (both calcium sulfite and sulfate) is given in Table 8.(10)

Table 8. Typical physical properties of wet FGD scrubber material. (10)

|

Property |

Calcium Sulfite (Unoxidized) |

Calcium Sulfate (Oxidized) |

|

Particle Sizing |

% |

% |

|

Sand Size Silt Size Clay Size |

1.3 90.2 8.5 |

16.5 81.3 2.2 |

Moisture Content : Dry FGD material is collected in a particle control device as a dry product and typically needs to be water conditioned (to approximately 10 percent) to reduce dusting during transport.(7) Dewatered calcium sulfate FGD scrubber material is typically stabilized or fixated before transport and use as a stabilized road base material. Prior to dewatering, the calcium sulfate slurry has a moisture content of approximately 60 percent. After dewatering, the moisture content is reduced to roughly 35 percent. Following stabilization or fixation, the FGD scrubber material has a moisture content of approximately 15 percent.(10)

Wet and Dry Unit Weight : The degree to which FGD scrubber material is treated (i.e. dewatered, stabilized, and fixated) influences the wet and dry unit weight. Table 9 shows the wet and dry unit weight for typical calcium sulfate FGD scrubber material in a dewatered, physically stabilized, and fixated condition.

Table 9. Physical characteristics of typical calcium FGD scrubber material.(10;11)

|

Physical Property |

Dewatered |

Stabilized |

Fixated |

|

Wet Unit Weight (kN/m3 ) (lb/ft3 ) |

14.9 - 15.7 (95 - 100) |

14.1 - 17.3 (90 - 110) |

14.1 - 18.1 (90 - 115) |

|

Dry Unit Weight (kN/m3 ) (lb/ft3 ) |

9.4 - 10.2 (60 - 65) |

9.4 - 10.2 (60 - 85) |

12.6 - 15.7 (80 - 100) |

Hydraulic Conductivity: As the moisture content of calcium sulfate FGD scrubber material is reduced through dewatering and stabilization, the hydraulic conductivity of the material is also reduced. Prior to dewatering, calcium sulfate slurry has a hydraulic conductivity of approximately 8 × 10-5cm/sec. After dewatering, the filter cake has a hydraulic conductivity of approximately 1 × 10-5 cm/sec; after stabilization the hydraulic conductivity is about 1 × 10-6 cm/sec; and after fixation the hydraulic conductivity may be as low as 5 × 10-8 cm/sec.(10) Compacted stabilized FGD material demonstrated a decrease in hydraulic conductivity with an increase in curing time.(12)

Compaction Characteristics : Depending on the amount of fly ash in a stabilized blend, maximum dry unit weight values of fixated FGD scrubber material can range from 10.4 to 15.2 kN/m3 (66 to 97 lb/ft3) at optimum moisture contents ranging from 12 to 37 percent when tested using the standard Proctor (ASTM D698)(13) test method.(12;14) Higher proportions of fly ash yield a higher maximum density.(12)

Compressive Strength : The compressive strength of most fixated FGD material base course mixtures continues to increase over time. Strength gain is more gradual with pozzolanic stabilized mixtures than mixtures stabilized with Portland cement or Class C fly ash. After 7 days, compressive strengths can range from 1400 to 2800 kPa (200 to 400 lb/in2) for pozzolanic stabilized mixtures and from 4100 to 6200 kPa (600 to 900 lb/in2) for mixtures stabilized with Portland cement or Class C fly ash. These strengths continue to increase over time and can exceed 13.8 MPa (2000 lb/in2) after one year. There is an increase in the unconfined compressive strength with an increase in the cement content of FGD stabilized mixes.(14)Compactive effort has a significant influence on the compressive strength of stabilized FGD mixtures.(14)

Durability : Durability testing of fixated FGD scrubber material may involve either freeze-thaw or wet-dry testing. Freeze-thaw testing should be performed in accordance with ASTM D560.(15) Wet-dry testing should be performed in accordance with ASTM D559.(16) A freeze-thaw study on stabilized calcium sulfite FGD material stabilized with fly ash and lime showed a relationship between higher sample water contents and decrease in strength with freeze-thaw cycling.(17) Increased cure time prior to first freeze improved freeze-thaw durability and a resistance to water infiltration. This study recommends a minimum of 60 days curing time be allowed before freezing temperatures are expected when using FGD material.(17)

DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

Mix DesignBase and subbase mix design for FGD scrubber sludge involves blending fixated FGD sludge with one or more stabilization reagents (lime, fly ash, or Portland cement). The stabilized mix design may also include coal bottom ash or aggregate. Using a series of trial mixtures, final mix proportions are selected on the basis of the results of both strength and durability testing according to ASTM C593 procedures.(18)

A minimum unconfined compressive strength of 2800 kPa (400 lb/in2) is recommended after ambient curing for between 14 and 28 days. If Portland cement is used as the stabilization reagent, some states require 4500 kPa (650 lb/in2) unconfined compressive strength after curing for 7 days.

Mixes containing fixated FGD scrubber material should be tested for moisture-density relationships and molded as close as possible to optimum moisture content and maximum dry density. If bottom ash is used as an aggregate, the ratio of FGD scrubber sludge to bottom ash is often in the 1.5:1 to 1:1 range. The addition of bottom ash has been shown to enhance the strength development of stabilized base mixes.

When using Portland cement as a stabilization reagent, type II (sulfate resistant) cement should be used. When a pozzolanic fly ash and quicklime are used to stabilize the FGD scrubber material, adequate strength can usually be achieved by the addition of up to 7 to 8 percent cement by weight of dry solids, or by adding more quicklime If a self-cementing fly ash is used as the FGD material fixation reagent, then adding a lower percentage of cement (possibly 3 to 4 percent) or the addition of more fly ash may be needed to achieve the required strength.

Structural Design

Designing pavement structures that include stabilized base or subbase layers that include FGD material typically follow AASHTO pavement design methods provided in the Guide for Design of Pavement Structures.(19) or the Guide for the Mechanistic-Empirical Design of New and Rehabilitated Pavement Structures.(20) The AASHTO methods account for the predicted loading (the number of 80 kN equivalent single axle loads), required reliability (degree of certainty that a design will function properly during the design life), serviceable life (ability to maintain quality during the pavement life), the pavement structure (characterized by the structural number), and subgrade support (related to the resilient modulus of the subgrade).(19)

A hierarchical approach in the mechanistic-empirical design method allows for varying levels of material characterization depending on project criteria. Mechanistic material properties such as dynamic modulus, resilient modulus, and Poisson's ratio are employed to evaluate pavement performance. The levels in the hierarchical system directly measure strength characteristics (level 1), use correlations to develop strength characteristics (level 2), or use typical material property default values (level 3). Chemically or cement stabilized base materials are included in the mechanistic-empirical design method.

Pavement design employing a structural number accounts for the relative strength of the constructed materials. The total structural support from the surface course, base course, and any subbase course equals the required structural number. Layer thicknesses are calculated using layer coefficients that define the structural support. The layer coefficients can be obtained from the relationship provided by AASHTO based on CBR or MR.(19)

When a Portland cement concrete roadway surface is to be designed with a stabilized base or subbase, the AASHTO structural design method for rigid pavements can be used.(19)

CONSTRUCTION PROCEDURES

Construction procedures for stabilized base and subbase mixtures in which fixated FGD scrubber material is used are the same as conventional pozzolanic stabilized bases and subbases.Material Handling and Storage

Fixated FGD scrubber material is typically stockpiled on a concrete pad at the power plant to allow for initial set of the material, typically less than a few days. The material can then be blended with additional reagent (such as lime or Portland cement), blended with bottom ash, boiler slag, or other aggregate, or transported and placed at a job site in the fixated condition.

Mixing, Placing, and Compacting

Plant mixing of FGD material for stabilized bases is recommended because of the greater control over the quantities of materials batched, which results in a more uniform mixture. Mixing in place of dewatered FGD scrubber material is not recommended because of the toothpastelike consistency.

To develop the design strength of a stabilized base mixture, the material should be well-compacted at the optimum moisture content. Fixated FGD scrubber materials should be delivered, placed, and compacted as soon as possible after mixing. This is particularly the case with mixtures in which Class C fly ash is used as an activator.

Fixated FGD scrubber base materials should be placed in layers that result in a compacted thickness between 10 and 22 cm (4 and 9 in). These materials should be spread in loose layers that are approximately 5 cm (2 in) thicker than the desired compacted thickness. The top surface of an underlying layer should be scarified prior to placing the next layer. Smooth drum, steelwheeled vibratory rollers are most frequently used for compaction, although satisfactory compaction results have also been obtained using smooth drum, steelwheeled static rollers. The smooth drum roller also seals the surface of the road base to minimize adverse impacts from rainfall.(2)

Curing

After placement and compaction, fixated FGD scrubber base material should be properly cured to protect against drying and assist in the development of in-place strength. An asphalt emulsion seal coat can be applied to the top surface of the stabilized base or subbase material. For most types of stabilized base materials, seal coat is applied within 24 hours after placement. Placement of asphalt paving over stabilized base is recommended within 7 days after the base has been installed. Unless an asphalt binder and/or surface course has been placed over the stabilized base material, vehicles should not be permitted to drive on the stabilized base until an in-place compressive strength of at least 2400 kPa (350 lb/in2) is achieved.(21)

Special Considerations

Cold Weather Construction Stabilized base materials containing fixated FGD scrubber material that are subjected to freezing and thawing conditions must be able to develop a certain level of cementing action and in-place strength prior to the first freeze-thaw cycle. For northern states, many state transportation agencies have established construction cut-off dates for stabilized base materials. These cutoff dates ordinarily range from September 15 to October 15, depending on the state, or the location within a particular state, as well as the ability of the stabilized base mixture to develop a minimum desired compressive strength within a specified time period.(21) A laboratory study on calcium sulfite FGD material recommends a minimum of 60 days curing time between compaction of the FGD material and the first freeze.(17)

Use of Self-Cementing Fly Ash with FGD material Stabilized base mixtures using self-cementing fly ash as an activator should be placed and compacted as soon as possible after mixing. Delays in placement and compaction of self-cementing fly ash mixes may significantly decrease the strength of the compacted stabilized base material.(22)

Crack Control Techniques Stabilized FGD base layers constructed with fly ash are less likely to produce reflection cracking in overlying pavement as is sometimes the case with Portland cement stabilized base layers. This is most likely due to a less stiff bond. Approaches for controlling or minimizing the potential effects of reflective cracking associated with stabilized base layers have been recommended by the ACAA.(21)

An approach to controlling or minimizing reflective cracking associated with shrinkage cracks in stabilized base materials is to saw cut transverse joints in the asphalt surface that extend into the stabilized base material to a depth of 75 to 100 mm (3 to 4 in). Joint spacing of 9 m (30 ft) have been suggested.(21) Joints should be sealed with a material such as hot poured asphaltic joint sealant.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

The use of FGD material in base material requires good management and care to ensure that the FGD material does not result in a negative impact on the environment. In particular, areas with sandy soils possessing high hydraulic conductivities and areas near shallow groundwater or drinking aquifers should be given careful consideration. An evaluation of groundwater conditions, applicable state test procedures, water quality standards, and proper construction are all necessary considerations in ensuring a safe final product.(23)WiscLeach is a modeling program specifically developed for coal combustion by-product reuse in highway applications. WiscLeach is available in the public domain and uses analytic methods to simulate two-dimensional flow and transport.(24) Factors found to have the greatest influence on concentrations in groundwater are depth to the groundwater table, thickness of a by-product layer, hydraulic conductivity of the least conductive layer in the vadose (unsaturated) zone, hydraulic conductivity of the aquifer, and initial trace element concentrations in the by-product layer.(24)

REFERENCES

A searchable version of the references used in this section is available here. A searchable bibliography of FGD scrubber material literature is available here.- Dockter BA, Jagiella DM. Engineering and environmental specifications of state agencies for utilization and disposal of coal combustion products. In: 2005 world of coal ash conference, Lexington, KY. 2005.

- Smith CL. First 100,000 tons of stabilized scrubber sludge in roadbase construction. In: Second international exhibition and conference for the power generation industries - POWER-GEN '89, New Orleans, LA. 1989.

- Smith CL. FGD sludge C coal ash road base: Seven years of performance. In: Proceedings of the 8th international coal and solid fuels utilization conference, Pittsburgh, PA. 1985.

- Amaya PJ, Booth EE, Collins RJ. Design and construction of roller compacted base courses containing stabilized coal combustion by-product materials. In: Proceedings of the 12th international symposium on management and use of coal combustion by-products. Electric Power Research Institute; Palo Alto, CA: 1997.

- Prusinski JR, Cleveland MW, Saylak D. Development and construction of road bases from flue gas desulfurization material blends. In: Proceedings of the eleventh international ash utilization symposium. Electric Power Research Institute; Palo Alto, CA: 1995.

- Saylak D, Estakhri CK. Stabilization of road bases containing coal combustion by-products sulfates and sulfites using high volume fly ash cement. In: 1999 international ash utilization symposium, Center for applied energy research. University of Kentucky; 1999.

- Berland TD, Pflughoeft-Hassett DF, Dockter BA, Eylands KE, Hassett DJ, Heebink LV. Review of handling and use of FGD material. Report nr 2003-EERC-04-04, Energy & Environmental Research Center, University of North Dakota; Grand Forks, ND: 2003.

- Kost DA, Bigham JM, Stehouwer RC, Beeghly JH, Fowler R, Traina SJ, Wolfe WE, Dick WA. Chemical and physical properties of dry flue gas desulfurization products. Journal of Environmental Quality 2005;34:676.

- Taha R, Saylak D. The use of flue gas desulfurization gypsum in civil engineering applications. In: Proceedings of utilization of waste materials in civil engineering construction. American Society of Civil Engineers; 1992.

- Smith CL. FGD waste engineering properties are controlled by disposal choice. In: Proceedings of conference on utilization of waste materials in civil engineering construction, New York, NY, American Society of Civil Engineers; 1992.

- Patton RW. Disposal and treatment of power plant wastes. In: Presented at the society of mining engineers fall meeting, salt lake city, UT. 1983.

- Butalia TS, Wolfe WE. Evaluation of permeability characteristics of FGD materials. Fuel 1999;78:149-52.

- ASTM D698-07e1 standard test methods for laboratory compaction characteristics of soil using standard effort (12 400 ft-lbf/ft3 (600 kN-m/m3)). In: Annual book of ASTM standards. ASTM; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2007.

- Taha R. Environmental and engineering properties of flue gas desulfurization gypsum. Transportation Research Record 1993;1424.

- ASTM D560-03 standard test methods for freezing and thawing compacted soil-cement mixtures. In: Annual book of ASTM standards. ASTM; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2003.

- ASTM D559-03 standard test methods for wetting and drying compacted soil-cement mixtures. In: Annual book of ASTM standards. ASTM; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2003.

- Chen X, Wolfe WE, Hargraves MD. The influence of freeze-thaw cycles on the compressive strength of stabilized FGD sludge. Fuel 1997;76(8):755-9.

- ASTM C593-06 standard specification for fly ash and other pozzolans for use with lime for soil stabilization. In: Annual book of ASTM standards. ASTM; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2006.

- AASHTO. Guide for design of pavement structures.: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials; Washington, DC, 1993.

- NCHRP 1-37A. Guide for mechanistic – empirical design of new and rehabilitated pavement structures. National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board; 2004.

- American Coal Ash Association (ACAA). Flexible pavement manual: Recommended practice - coal fly ash in pozzolanic stabilized mixtures for flexible pavement systems. 1991:128 p.

- Thornton SI, Parker DG. Construction procedures using self-hardening fly ash. Report nr FHWA/AR/80, 004 Federal Highway Administration; Washington, DC: 1980.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Using coal ash in highway construction - A guide to benefits and impacts. ; Report nr EPA-530-K-002:ID: 151. 2005.

- Li L, Benson CH, Edil TB, Hatipoglu B. Groundwater impacts from coal ash in highways. Waste and Management Resources 2006;159(WR4):151-63.

FGD Scrubber Material - Flowable Fill

Note: The use of flue gas desulfurization (FGD) material as flowable fill is an emerging application area. Published research and case studies on this subject are limited. As such, the use of FGD for this application is not well documented, and any use of FGD as a flowable fill should be considered somewhat experimental. Publication of such uses and laboratory research would aid in the understanding of FGD’s performance as a flowable fill.INTRODUCTION

FGD material (both wet and dry) are being researched as a replacement for fly ash in flowable fill material. The cementitious reactions that occur with FGD material are well-suited for flowable fill applications.(1;2) Low unit weight and sufficient shear strength make FGD flowable fill a suitable alternative to commonly used compacted earth backfills.(3;2) Research conducted at Ohio State University (OSU) investigated the use of FGD material in flowable fill, the results of these studies make up the majority of this user guideline.Flowable fill is used as a self-leveling, self-compacting backfill material. Typical flowable fill mixtures include filler material, cementitious material, and can contain mineral admixtures. Filler material usually consists of fine aggregate such as sand, but some flowable fill mixes may contain equal portions of coarse and fine aggregates.(4)

The use of flowable fill as a highway construction material is becoming more widespread throughout the United States. Most state transportation agencies have used flowable fill mainly as a trench backfill for storm drainage and utility lines on street and highway projects. Other applications for flowable fill include filling behind retaining walls, building excavations, underground storage tanks, abandoned sewers and utility lines, and slab jacking.

Flowable fill is considered a controlled low strength material (CLSM) according to ACI 116R as long as the compressive strength is less than 8270 kPa (1200 lb/in2).(5;6;7) In high strength CLSM applications, the strength of flowable fill mixes can range from 1380 to 8270 kPa (200 to 1200 lb/in2), depending on the design requirements. The desired range of compressive strength in flowable fill mixtures depends on whether the hardened material is designed to be removed in the future. The ultimate strength for excavatable flowable fill should not exceed 1035 kPa (150 lb/in2) or jack hammers may be required for removal.(4) For flowable fill mixes used in higher bearing capacity applications, such as structural fill or temporary support of traffic loads, higher compressive strengths can be designed.

ENGINEERING PROPERTIES

Engineering properties of FGD flowable fill mixes that are of interest include compressive strength, flowability, stability, bearing capacity, modulus of subgrade reaction, lateral pressure, time of set, bleeding and shrinkage, unit weight, and hydraulic conductivity. Unfortunately all of these properties have not yet been investigated and published in the literature.A wet and dry FGD flowable fill testing program conducted at Ohio State University investigated unconfined compressive strength (UCS), flowability, unit weight, penetration resistance, and FGD flowable fill mix design. The tests were conducted on a wet fixated scrubber sludge and dry FGD generated with a lime sorbent(2;3).

Compressive Strength: Typical desired value for 28-day unconfined compressive strength of flowable fill ranges from 172 to 410 kPa (25 to 60 psi). The lower limit of this range corresponds to the strength needed to support construction vehicles while the upper limit strength is still excavatable. Test results showed that strength increased with curing time and that strength was directly related to water content.(3) The 28 day strength of wet fixated FGD scrubber sludge, with an additional 6 percent cement, was 1041 kPa (150 psi), while the addition of 6 percent lime produced a 28 day strength of 379 kPa (55 psi).(2) Dry FGD flowable fill unconfined compressive strength vs. time for varying water contents is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Unconfined compression strength of dry FGD flowable fill vs. time at varying water contents.(3)

Table 10. Flowability test and dry unit weight of varying dry FGD samples.(3)

|

Water Content (%) |

Flow mm (in.) |

Dry Unit Weight kN/m3(pcf) |

|

65.0 72.5 77.0 |

152 (6) 203 (8) 330 (13) |

8.96 (57) 8.49 (54) 8.96 (57) |

Penetration Resistance: Long term penetration resistance characteristics of FGD material used as a flowable fill are comparable to conventional cement-based flowable fill. Short term penetration resistance characteristics of dry FGD material and water mixes showed penetration resistance values measured with ASTM D6024(12) less than 689 kPa (100 psi) after 24 hours and less than 1375 kPa (200 psi) after 144 hours (6 days).(3)Early penetration resistance can be increased with the addition of cement, lime, or admixture. In general, larger proportions of cement, lime, or admixture in the FGD flowable fill mixes cause flowable fill to harden faster, although higher longer term strength should be expected.(3)

DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

Mix DesignFlowable fill mixtures traditionally are proportioned by trial and error. Most specifications for flowable fill provide quantities of constituents that produce an acceptable product, although some specifications are performance-based (usually based on a maximum compressive strength) and leave the proportioning up to the material supplier. ACI provides guidance for the proportioning of flowable fill mixtures.(6)

Mix designs for FGD flowable fill can be a simple as FGD and water or can contain cement, lime, and/or admixtures in varying amounts to achieve desired properties. Dry FGD and water mixes, at water contents between 65 and 77 percent, showed acceptable flowability and long term strength for flowable fill, but short term penetration resistance may be too low for some construction projects. Mixes containing dry FGD material, water, cement and/or lime (6 to 10 percent), and admixtures (1.3 to 5.9 percent) showed excellent flowability and long term strength along with achieving a penetration resistance of 2750 kPa (400 psi) in one to two days.(13)

Wet fixated FGD scrubber sludge, with a fly ash to filter cake ratio of 1.25:1 with an additional 5 percent lime, were used in flowable fill mix designs. The wet fixated FGD flowable fill mix designs were at a water content of 82.5 to 84 percent, and had additional cement or lime added at 6 percent of the dry unit weight of the FGD material. Although these mixes had good flowability, the short term (24 hr) penetration resistance for the 6 percent lime mix may be too low for some applications and the 6 percent cement mix developed too much long term strength for excavatable flowable fill.(2)Therefore, wet fixated FGD mixes may require admixtures to reduce initial set time and a reduction in cement to reduce long term strength. Long term strength, even beyond 28 days, may need to be investigated if future excavation is a required.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Although not specifically from leachate studies on FGD flowable fill, FGD material leachate show pH typically exceeds 11.0, and some sources can exceeded the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act limit of 12.5 for toxic waste, although this high leachate pH is expected to decrease over time.(14;15) The high pH of FGD grout has been used beneficially to neutralize acid mine drainage.(16;17) The low hydraulic conductivity of flowable fills in general reduces the rate at which water permeates and trace elements leach from flowable fill. Trace element concentrations in FGD leachate are generally low.(14)UNRESOLVED ISSUES

Further research is needed on both the mechanical and environmental aspects of FGD flowable fill. Due to the variety of FGD systems, acceptable reuse from one FGD product and source does not imply universal acceptability. Research is needed on FGD flowable fill with respect to: stability (friction angle), bearing capacity (CBR), corrosivity, resilient modulus, modulus of subgrade reaction, lateral pressure development, bleeding and shrinkage, and hydraulic conductivity. In addition, research is needed in the interaction between admixture, cement, and the properties of FGD flowable fill.REFERENCES

A searchable version of the references used in this section is available here. A searchable bibliography of FGD scrubber material literature is available here.- NETL National Energy Technology Laboratory. Commercial use of coal utilization by-products and technology trends. Department of Energy Office of Fossil Energy; Washington, DC: 2003.

- Butalia TS, Wolfe WE, Zana B, Lee JW. Flowable fill using flue gas desulfurization material. Journal of ASTM International 2004;1(9):1-12.

- Butalia TS, Wolfe WE, Lee JW. Evaluation of a dry FGD material as a flowable fill. Fuel 2001;80:845-50.

- Smith A. Controlled low-strength material. Concrete Construction 1991:389-98.

- ACI Committee 116. Cement and concrete terminology. Report nr 116R-00, American Concrete Institute (ACI), Detroit, Michigan: 2000.

- ACI Committee 229. Controlled low strength materials (CLSM). Report nr 229R-99, American Concrete Institute (ACI), Detroit, Michigan:1999.

- Ramme BW, Tharaniyil M. Coal combustion products utilization handbook. We Energies; Milwaukee, WI: 2004.

- ASTM C143/C143M-05a standard test method for slump of hydraulic-cement concrete. In: Annual book of ASTM standards. American Society for Testing and Materials; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2005.

- ASTM C939-02 standard test method for flow of grout for preplaced-aggregate concrete (flow cone method. In: Annual book of ASTM standards. American Society for Testing and Materials; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2002.

- Balsamo NJ. Slurry backfills – useful and versatile. Public Works, April 1987;118:58-60.

- ASTM D6103-04 standard test method for flow consistency of controlled low strength material (CLSM). In: Annual book of ASTM standards. ASTM; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2007.

- ASTM D6024-02 standard test method for ball drop on controlled low strength material (CLSM) to determine suitability for load application. In: Annual book of ASTM standards. American Society for Testing and Materials; West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: 2002.

- Lee JW, Butalia TS, Wolfe WE. Potential use of FGD as a flowable-fill. In: 1999 international ash utilization symposium, Center for applied energy research. University of Kentucky; 1999.

- Kost DA, Bigham JM, Stehouwer RC, Beeghly JH, Fowler R, Traina SJ, Wolfe WE, Dick WA. Chemical and physical properties of dry flue gas desulfurization products. Journal of Environmental Quality 2005;34:676.

- Cheng C-, Tu W, Zand B, Butalia TS, Wolfe WE, Walker H. Beneficial reuse of FGD material in the construction of low permeability liners: Impacts on inorganic water quality constituents. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2007;133(5):523-31.

- Stuart BJ, Novak G, Payne H, Togni CS. Use of flue gas desulfurization by-product for mine sealing and abatement of acid mine drainage. In: 1999 international ash utilization symposium, Center for applied energy research. University of Kentucky; 1999.

- Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). Flue gas desulfurization by-products: Composition, storage, use, and health and environmental information. EPRI, Inc; Palo Alto, CA: 1999.